Governor Appointments and Central Bank Independence

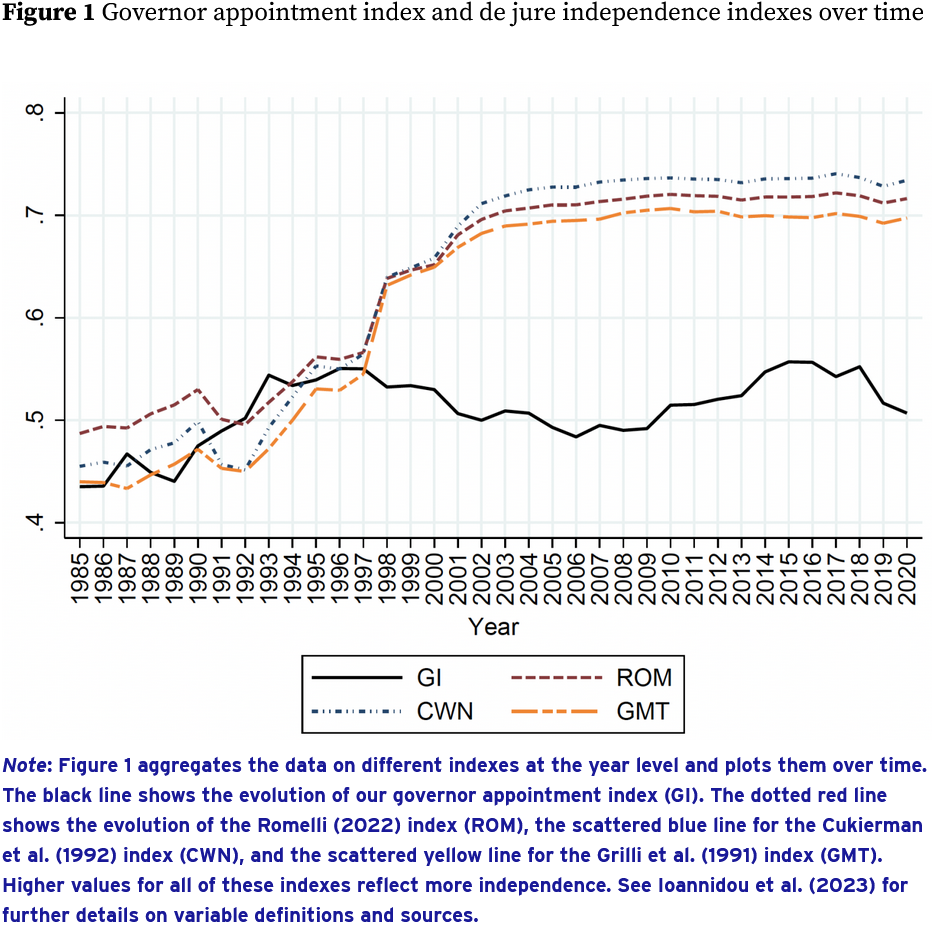

Since the late 1980s, many countries have reformed the legal frameworks governing central banks to protect these institutions from undue political influence and safeguard price (and financial) stability (Grilli et al. 1991, Cukierman et al. 1992, Romelli 2022).

However, legal or de jure independence does not necessarily translate into actual or de facto independence. Laws are incomplete, and even when the law is explicit, actual practice may deviate. Policy reforms may also give rise to a ‘seesaw effect’ – when a policy reform takes place in one dimension but the political equilibrium remains largely unchanged, politicians may try to use a different instrument to attain the goal previously targeted with the instrument that is being reformed (Acemoglu et al. 2008). One way in which politicians may seek to retain control over monetary policy is by ‘getting their own people into the top jobs’. Anecdotal evidence consistent with this idea is plentiful. For example, The Economist noted a few years ago that “President Donald Trump has demanded that interest rates should be slashed, speculated about firing the boss of the Federal Reserve […] India’s government has replaced a capable central-bank chief with a pliant insider who has cut rates ahead of an election […] Rather than win by force of argument, they are seeking an edge by getting their own people into the top jobs” (The Economist, 13 April 2019).

In a new paper (Ioannidou et al. 2023), we examine whether central bank governor appointments have become more or less political, following significant legal reforms aiming to insulate the central bank and its governor from political interference. We define a politically motivated governor appointment as one where the appointment is skewed towards a candidate who is more loyal to the executive making the appointment rather than the central bank mandate. Furthermore, we study whether politically motivated appointments relate to central bank policy outcomes. We should clarify upfront that our paper does not inform the debate concerning the appropriate, or even optimal, level of central bank independence. We focus on central bank governors because of their disproportionate importance in running the central bank.

Narratives

It is natural to expect that if the original goal of improving de jure central bank independence were to reduce political interference, de jure independence should be negatively correlated with politically motivated appointments. Therefore, if the stated goal is to make the central bank more politically independent, then we should expect less politically motivated governor appointments so that de jure independence more convincingly becomes de facto independence. This intuition suggests that the correlation between metrics of de jure independence and more independent governor appointments should be positive.

However, a positive correlation is not the only possible outcome. Political processes have a status quo bias, either because political habits are hard to change or because laws are very hard to reverse. Politicians used to appoint close allies at the central bank might look for alternative ways to circumvent the enacted central bank independence legislation, especially when reversing such legislation is difficult. Therefore, the correlation between de jure independence and more independent governor appointments may disappear, or even turn negative, if politicians actively seek to reverse the legal reforms by appointing central bank governors with close ties to the government.

Politically motivated governor appointments: measurement

To examine which of these narratives better describes the data, we hand-collect systematic information on 316 central bank governor appointments in 57 countries between 1985 and 2020. We combine three complementary sources of information:

- The first source involves biographical information. This includes ties with the executive branch of the government through prior employment, shared ideology with the ruling party or personal links (e.g. known friendships and family ties) as well as information about the nature of succession (e.g. whether the governor replaces a governor who was forced to resign) and the formal credentials of the governor (i.e. education and prior work experience).

- The second source of information captures the perception of the international press on the political independence (or lack thereof) of the appointed governor.

- The third source of information captures the opinions of independent academic experts about the perceived political independence of a particular governor at the time of appointment in their respective countries via a large-scale survey. We sent the survey to 587 academics with expertise in macroeconomics or finance and obtained a response rate of 49.2%.

We compiled these three sources of information into an index characterising whether, at the time of appointment, a governor was perceived as being independent of the executive and elected politicians.

Governor appointments and central bank independence: New insights

We do not find support for the hypothesis that central bank governor appointments have become more independent over time, despite significant improvements in de jure central bank independence. There is no discernible relation between our governor appointment index and measures of de jure independence, including specific institutional reforms precisely targeting the appointment, term in office, and dismissal of central bank governors. This result can be observed visually in Figure 1 and sustains in regression analysis controlling for (fixed) country characteristics as well as instrumental variable analysis using the regional diffusion of de jure central bank independence as an instrument (similar, in spirit, to Acemoglu et al. 2019).

Furthermore, not only have central bank governor appointments not become more independent on average, but our results further show that they may have become more political as central banks are given more operational independence. The relation between our governor appointment index and legal reforms that aim to insulate the governor from political interference turns strongly negative when central banks are given more policy or financial independence, and their operations become less transparent.

These results indicate that governments may actively seek to undo legal reforms and undermine de facto central bank independence through the appointment process.

Central bank independence and policy outcomes: A reappraisal

A pressing question that arises from the finding that de facto central bank independence is not associated with de jure central bank independence is whether de jure and de facto independence correlate with worse policy outcomes.

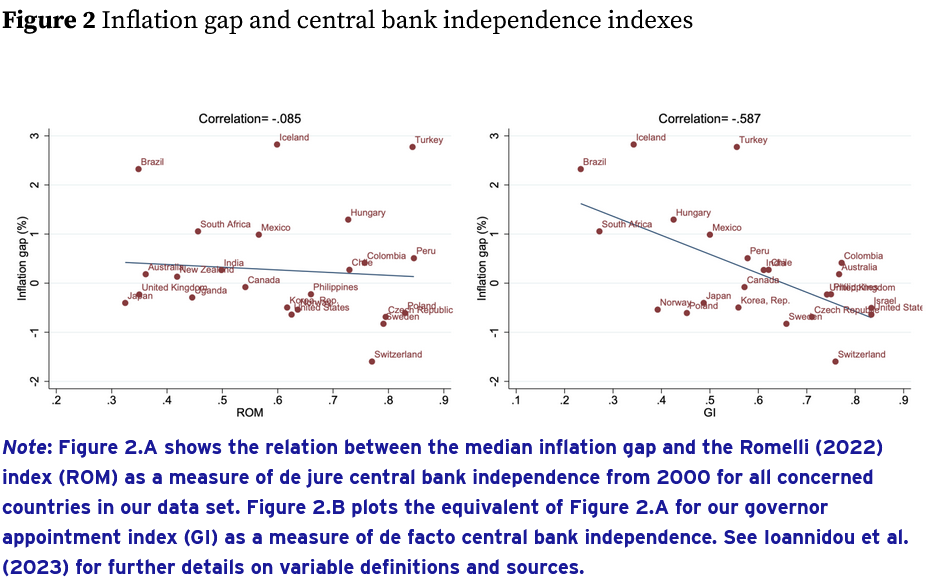

Alesina and Summers (1993) present early evidence that more independent central banks tend to be associated with lower inflation rates. More recent empirical evidence, however, fails to support this relation (e.g. Balls et al. 2018; Haldane 2020). One possible reason is that the earlier Alesina and Summers (1993) finding is not robust or disappears once central banks begin targeting inflation. Another possible explanation is that de jure independence does not reflect de facto independence.

Our results support the second explanation. We find that while the negative relation between inflation and de jure central bank independence breaks down when we extend the sample to more recent years or/and a larger set of countries, the negative relation between inflation and central bank independence sustains if we use de facto independence, as measured by our governor appointment index. The results also hold when we restrict attention to countries with explicit inflation targets. In Figure 2, we can see that the mean deviation between inflation and the inflation target has a zero correlation with de jure central bank independence but an economically significant negative correlation with de facto central bank independence. These results show that de facto central bank independence correlates more strongly with central bank inflation outcomes than de jure independence.

Furthermore, the time inconsistency problem leading to inflation bias can also be accompanied by a similar ‘financial instability bias’ by favouring more lax banking regulation and supervision. Since many central banks have (explicit or implicit) responsibilities in the area of financial stability, a related question that arises is whether de jure and de facto central bank independence correlate with financial stability outcomes. Our data confirm that, unlike de jure independence, de facto independence exhibits a negative correlation with financial instability (as captured by, e.g. the likelihood of experiencing a banking crisis).

Policy implications

Our findings have important policy implications. First, undue political influence on central bank appointments reduces the credibility of a central bank and, therefore, potentially allows the time inconsistency problem to resurface, regardless of the level of de jure central bank independence.

Second, following the Global Crisis and the Covid pandemic, central bank mandates have expanded from inflation targeting to financial stability, liquidity provisions, and quantitative easing that increased central bank balance sheets to historical records. In addition to these macro-prudential and financial stability roles, central banks have been taking over new responsibilities in banking supervision and bank resolution. Their powers are only expected to expand as they develop policies towards climate finance and digital currencies (Skinner 2021). The design of the institutional architecture of a central bank and central bank decision-making will need to be further scrutinised for political accountability and credibility in the future (Tucker 2019).

Our results illustrate that legal independence is not sufficient to guarantee that the central bank is not captured by political interests. Recent evidence shows that central banks are receptive to political pressures (Binder 2021, Goncharov et al. 2021) and care actively about justifying their policies (Kempf and Pastor 2020). Our results illustrate one channel via which external pressure or interference may occur – political appointments. As central bank powers increase, it is likely that incentives to appoint political allies, with the explicit or implicit aim to affect future central bank policies, will increase.

References

Acemoglu, D, S Johnson, J Robinson, and P Querubin (2008), “When does policy reform work? The case of central bank independence”, VoxEU.org, 25 June.

Acemoglu, D, S Naidu, P Restrepo, and J A Robinson (2019), “Democracy does cause growth”, Journal of Political Economy 127 (1): 47-100.

Alesina, A and L H Summers (1993), “Central bank independence and macroeconomic performance: some comparative evidence”, Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 25 (2): 151-162.

Balls, E, J Howat, and A Stansbury (2018), “Central bank independence revisited: After the financial crisis, what should a model central bank look like?”, Harvard Kennedy School M-RCBG Associate Working Paper No. 87.

Binder, C C (2021), “Political pressure on central banks”, Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 53 (4): 715-744.

Cukierman, A, S B Web, and B Neyapti (1992), “Measuring the independence of central banks and its effect on policy outcomes”, World Bank Economic Review 6 (3): 353-398.

Goncharov, I, V Ioannidou, and M C Schmalz (2021), “(Why) do central banks care about their profits?”, Journal of Finance, forthcoming.

Grilli, V, D Masciandaro, and G Tabellini (1991), “Political and monetary institutions and public financial policies in the industrial countries”, Economic Policy 6 (13): 341-392.

Haldane, A (2020), “What has central bank independence ever done for us?”, Keynote Speech at the UCL Economists’ Society Economics Conference.

Ioannidou, V, S Kokas, T Lambert, and A Michaelides (2023), “(In)dependent central banks”, CEPR Discussion Paper No. DP17802.

Kempf, E, and L Pastor (2020), “Fifty shades of QE: Central bankers versus academics”, VoxEU.org, 5 October.

Laeven, L and F Valencia (2013), “Systemic banking crises database”, IMF Economic Review 61 (2): 225-270.

Romelli, D (2022), “The political economy of reforms in central bank design: Evidence from a new dataset”, Economic Policy 37 (112): 641-688.

Skinner, C P (2021), “Central bank activism”, Duke Law Journal 71: 247-328.

Tucker, P (2019), Unelected Power, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

This post is co-written with Vasso Ioannidou, Sotirios Kokas, and Alexander Michaelides and also published in VoxEU.