Decentralizing Bank Supervision

The supervisory architecture of the financial system determines how oversight responsibilities and powers are distributed among policy institutions. In Europe, the global financial crisis (GFC) sparked an intense debate over the optimal supervisory architecture, focused on restoring trust in the banking sector and enhancing the resilience of the financial system. In 2014, the European Single Supervisory Mechanism (SSM) assumed central supervision of the largest banks across the euro area, drawing on lessons learned from the GFC and the sovereign debt crisis.

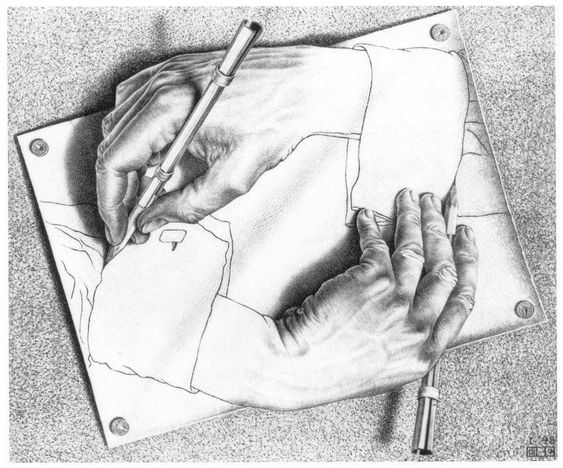

In a new paper, we offer new perspectives on the relationship between a supervisory architecture and micro-prudential supervision, by examining an organizational reform undertaken in 2015 within the China Banking Regulatory Commission (CBRC). The reform we assess shifted supervision of bank branches from the national to the prefecture level.

Why does the supervisory architecture matter?

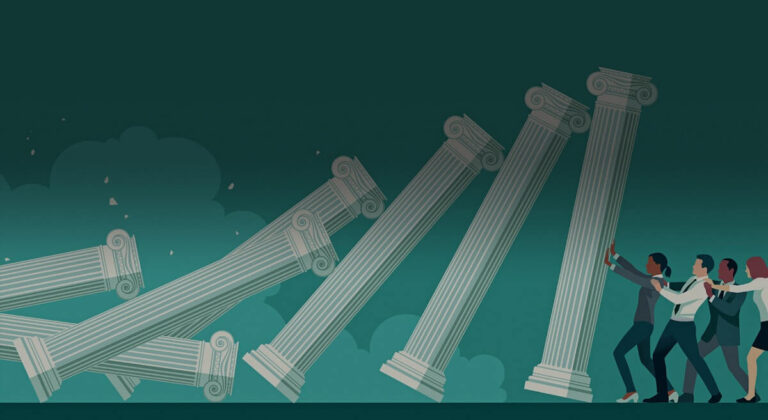

The principal trade-off between decentralized (local) and centralized supervision lies in incentives and information. Central supervisors may make better decisions with a broader view of the banking sector and economy, while local supervisors may prioritize local (political and economic) interests, leading to biased oversight. However, local supervisors have better access to information about the banks they oversee and can specialize in local conditions, while central supervisors face challenges in collecting this information due to physical and institutional distance.

The Chinese banking sector and the CBRC reform of 2015

China is the largest banking sector in the world with about $40 trillion in assets (as of 2020). In 2015, China undertook reforms to decentralize supervision for those branches of banks classified as ‘local’ but not for branches belonging to ‘national’ banks (that is, branches supervised by the central supervisor in Beijing). Prior to 2015, all branches were supervised in a hub-and-spoke system in which information was collected by local supervisors, but decisions were made jointly with the central supervisory authority. The central supervisor had a potential informational disadvantage as the information was provided by the local supervisor. Subsequently, the reforms fully transferred responsibilities and powers for branches of local banks to local supervisors. Importantly, the reform did not change the overall objective of supervision, as local supervisors are formally subordinated to the central supervisor and fully accountable to the latter. However, local supervisors might be subject to the different biases, thus creating a tension between incentives and information. An interesting institutional feature in this regard is that local supervisors operate at the prefecture level in China: there are more than 300 prefectures that have a designated supervisor who oversees bank activities in the prefecture.

We make use of a large data set covering 5,429 branches over a 10-year window around the 2015 reform (period between 2010 and 2020). We focus on supervisory decisions using a novel bank branch and supervisory-office-level data on enforcement actions.

Our findings on supervisory activity and bank lending

We have three sets of findings:

- Branches of local banks are more likely to receive enforcement actions following the reform as compared to branches of national banks. Economically, these branches were 57% to 80% more likely to get an enforcement action after the 2015 reform, indicating that local supervision is significantly tighter than central supervision.

- Branches of local banks are more conservative in their lending decisions after the organizational reform. That is, we find that they require a higher compensation for taking on risk and reduce the amount they lend.

- These decisions at the loan level have aggregate consequences: prefectures with a higher share of branches from local banks experienced lower credit growth in the aftermath of the reform.

Our findings on information versus incentives

We find support for both the informational and incentive channels. Under the hub-and-spoke system in China, information about a branch is collected from the supervisory office of the prefecture where the branch is located; this information is then shared (or not) with the central supervisor. We therefore approximate the informational loss by the geographical distance between Beijing (the location of the central supervisor) and the capital of the prefecture where a branch and its local supervisor are. We show evidence that supervisory interventions increase for branches with a higher informational loss under centralized supervision.

As for incentives, we first examine the government ownership of banks and find evidence suggesting that local supervisors pursue local political interests. Furthermore, we observe that local supervisors care relatively more about local economic interests. That is, local supervisors tend to ignore effects materializing outside their regulatory perimeter. Local supervisors intervene more stringently at a specific branch when local financial risk is elevated. Local supervisors also intervene less stringently at the branches for which the associated bank has its main operations outside the branches’ prefecture.

Together, our findings support the idea that decisions of local supervisors are partly driven by their local political and economic interests. However, our estimates quantitatively suggest that the magnitude of these biases is muted compared to the informational channel.

Policy implications

Besides offering novel evidence on enforcement activity from the largest banking sector worldwide, our study has implications for the design of an optimal supervisory architecture.

In the euro area, bank supervision for larger banks moved toward centralization in the aftermath of the GFC as it was considered to have significant benefits by lowering the influence of local interests. Prior work shows support for this view that supervisory stringency improved for the large banks included in the SSM. Our analysis of the 2015 reform in China complements the picture, showing that for smaller (local) banks, decentralized supervision may be preferable. Both lines of research justify the design of the SSM where allocation to the central supervisor primarily depends on bank size.

In the United States, prior work further shows that the stronger effectiveness of federal supervision over state supervision is explained by different weights given by supervisors to local economic conditions and, to some extent, differences in supervisory capacity. Our analysis rather highlights that, in China, the gains from information collection may outweigh costs of local incentives when all supervisory offices are subject to the same hierarchical authority.

This post is co-written with Di Gong and Wolf Wagner and also published in Oxford Business Law Blog.