Politics and the Finance-Growth Nexus

2022 started pretty well with the acceptance (on January 2!) of my paper “Banks, Political Capital, and Growth” at the Review of Corporate Finance Studies. In this post, I’d like to discuss its content and also share my gratitude for having two great co-authors, Wolf Wagner and Eden Zhang.

We study the consequences of banks’ political connectedness for economic activity. We focus on the subset of banks that donate to candidates in US congressional elections and exploit close election outcomes as plausible exogenous changes in banks’ political capital.

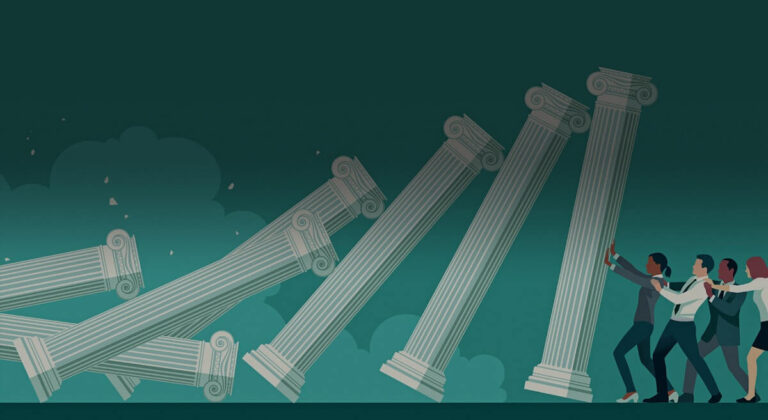

We first document that aggregate shocks to banks’ political capital produce larger subsequent changes in output growth in the regions where these banks operate. A region’s output growth increases by 0.56 percentage point when the banks active in the region experience a positive shock to their political capital due to close election outcomes. Political capital associated with powerful congressional committee members drives a significant part of this growth effect. However, we also find that it is temporary, vanishing rapidly after the election.

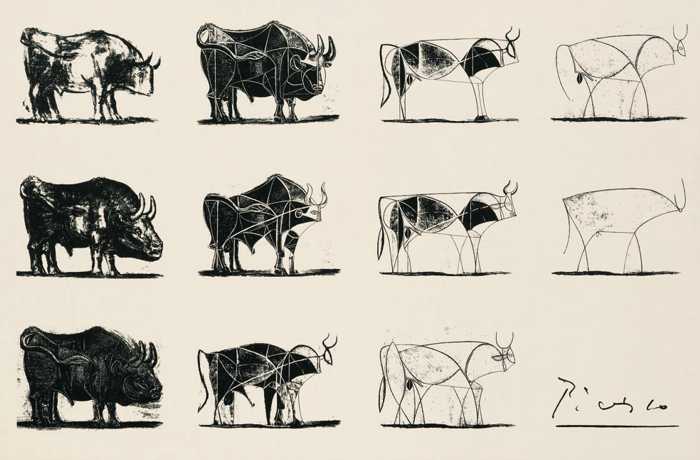

We then show that this growth effect is primarily due to relative sclerosis. There is fewer restructuring in the real economy and this is not accompanied by higher productivity. Regions experiencing positive shocks to their banks’ political capital have lower establishment exits and, similarly, fewer job losses in their real sector. However, we do not find that positive political capital shocks result in many more establishment entries as well as in more job creation and reallocation. Studying wages and patents also does not provide any evidence of productivity enhancement. Taken together, these findings suggest that banks’ investment in political capital produces short-term improvement in the real economic activity, mostly by supporting incumbent firms rather than by fostering a Schumpeterian process of creative destruction.

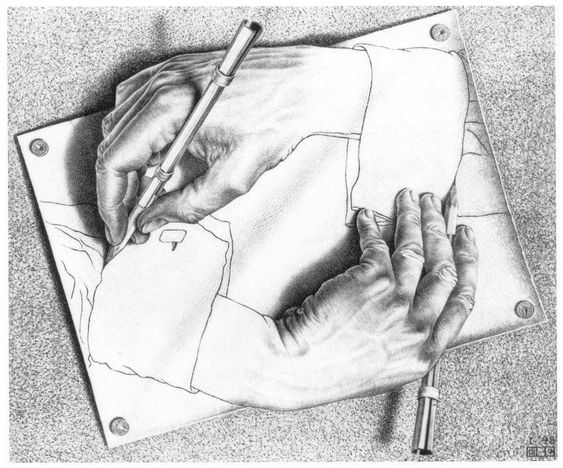

Finally, we present some evidence indicating that political connections incentivize banks to ease lending conditions for firms. Banks experiencing a positive shock to their political capital issue more loans and reduce interest rates, particularly so for riskier borrowers. The results are consistent with the idea that political connectedness magnifies the moral hazard problem in banking—that is, politically connected banks take on extra risks because their ties to elected politicians may protect them (especially when things get bad).

Collectively, our findings reveal that, although the interference between banks and (powerful) politicians appears beneficial for the US economy at first sight, these benefits are short lived and directed toward existing firms. Banks’ political connectedness may thus create barriers to entry for firms, instead of fostering a productivity-enhancing reallocation of resources that would be the sign of a well-functioning banking sector.

The code, data and reproducibility certificate (from Cascad) of the paper are available here.